GEOLOGY : The Mantle

What is mantle in geology?

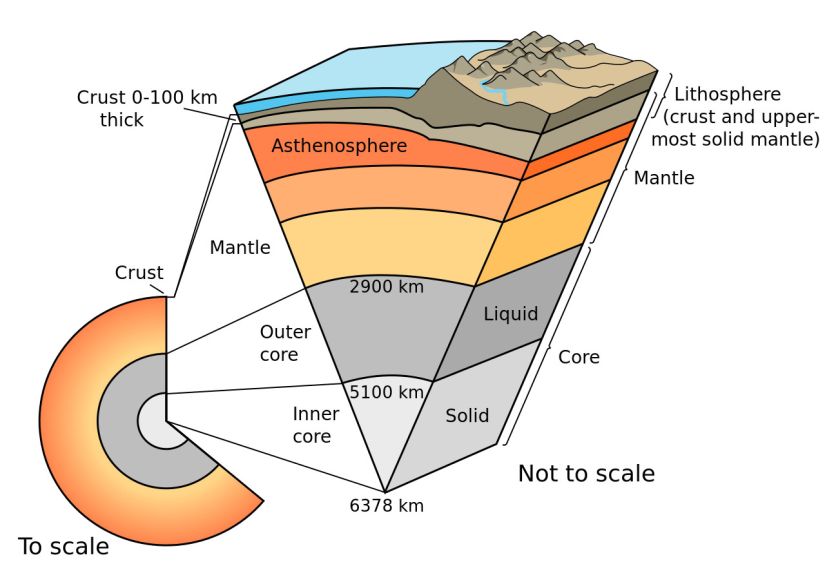

GEOLOGY : The Mantle : The majority of the interior of the Earth is made up of the mantle. The Earth’s thin exterior layer, the crust, and its deep, extremely hot core are separated by the mantle. The mantle makes up a staggering 84% of the entire volume of the Earth and is roughly 2,900 kilometers (1,802 miles) deep.

Iron and nickel swiftly separated from other rocks and minerals when Earth started to take shape around 4.5 billion years ago, forming the planet’s core. The early mantle was the molten material that encircled the core.

Mantle cooling occurred over millions of years. “Outgassing” is the process of water contained inside minerals erupting with lava. The mantle solidified as more water was outgassed.

The majority of the rocks that make up the Earth’s mantle are silicates, a large class of substances with a common silicon and oxygen structure. Olivine, garnet, and pyroxene are examples of common silicates discovered in the mantle. Magnesium oxide is the other main form of rock that can be found in the mantle. Other mantle constituents include calcium, salt, potassium, calcium, aluminum, and iron. The mantle’s temperature ranges widely, from 1000 °C (1832 °F) near its boundary with the crust to 3700 °C (6692 °F) near its boundary with the core. Heat and pressure in the mantle typically rise with depth. Geothermal gradient serves as a gauge for this rise. The geothermal gradient typically ranges from 1° Fahrenheit per 70 feet of depth to roughly 25° Celsius each kilometer.

The mantle’s viscosity also fluctuates considerably. The majority of it is solid rock, although around tectonic plate borders and mantle plumes, it is less viscous. There are soft mantle rocks that can move plastically under intense pressure and depth over the span of millions of years. The distribution of heat and material in the Earth’s mantle influences its topography. Plate tectonics is driven by mantle activity, which also contributes to earthquakes, seafloor spreading, volcanoes, and orogeny (mountain-building).

The mantle is divided into several layers: the upper mantle, the transition zone, the lower mantle, and D” (D double-prime), the strange region where the mantle meets the outer core.

GEOLOGY : The Mantle

Upper Mantle

From the crust, the upper mantle reaches to a depth of approximately 410 kilometers (255 miles). Despite being mainly solid, the upper mantle’s more pliable portions support tectonic action.

The lithosphere and the asthenosphere are two regions in the Earth’s interior that are frequently identified as separate sections of the upper mantle.

Lithosphere

The lithosphere is the Earth’s solid outer layer, which reaches a depth of around 100 kilometers (62 miles). The brittle upper part of the mantle and the crust together make up the lithosphere. The lithosphere is the layer of the Earth that is both the coolest and the stiffest.

Tectonic activity is the most well-known characteristic of the Earth’s lithosphere. The interaction of the enormous lithosphere slabs known as tectonic plates is referred to as tectonic activity. The North American, Caribbean, South American, Scotia, Antarctic, Eurasian, Arabian, African, Indian, Philippine, Australian, Pacific, Juan de Fuca, Cocos, and Nazca tectonic plates make up the lithosphere.

The Mohorovicic discontinuity, or simply the Moho, is the boundary between the crust and the mantle in the lithosphere. Due to the fact that not all areas of the Earth are equally balanced in isostatic equilibrium, the Moho does not exist at a uniform depth. The physical, chemical, and mechanical contrasts that allow the crust to “float” atop the occasionally more pliable mantle are referred to as isostasy. The Moho is located 32 kilometers (20 miles) beneath continents and eight kilometers (5 miles) beneath the ocean.

Lithospheric crust and mantle are distinguished by different types of rocks. Gneiss (continental crust) and gabbro are the two main components of the lithospheric crust (oceanic crust). Peridotite, a rock mostly composed of olivine and pyroxene, is what distinguishes the mantle beneath the Moho.

Asthenosphere

The weaker, denser layer below the lithospheric mantle is known as the asthenosphere. It is between 62 miles and 410 kilometers (100 miles) below the surface of the Earth. Because of the asthenosphere’s extreme heat and pressure, rocks begin to weaken and partially melt, turning semi-molten.

Compared to the lithosphere or lower mantle, the asthenosphere is far more ductile. A solid material’s capacity to stretch or deform while under stress is measured by ductility. The lithosphere-asthenosphere boundary (LAB), which is where geologists and rheologists—scientists who study the flow of matter—mark the difference in ductility between the two layers of the upper mantle, is generally more viscous than the lithosphere.

The process of plate tectonics, which is connected to continental drift, earthquakes, the formation of mountains, and volcanoes, is caused by lithospheric plates moving extremely slowly as they “float” on the asthenosphere. In actuality, the asthenosphere itself has melted into magma, which is what appears as lava when volcanic cracks erupt.

Of course, because the asthenosphere is not a liquid, tectonic plates are not actually floating. Only the borders and hot areas of tectonic plates are prone to instability.

GEOLOGY : The Mantle

Transition Zone

Rocks change dramatically between 410 kilometers (255 miles) and 660 kilometers (410 miles) below the surface of the Earth. The mantle’s transition area is here.

Rocks in the transition region don’t melt or decay. Instead, they undergo significant modifications in their crystalline structure. Rocks become incredibly thick.

The transition zone stops substantial material transfers between the upper and lower mantle. Some geologists believe that the transition zone’s greater rock density prevents subducted lithosphere slabs from detaching deeper from the mantle. These massive tectonic plate fragments remain stationary in the transition zone for millions of years before mixing with other mantle rock and eventually returning to the upper mantle as a component of the asthenosphere, erupting as lava, becoming a component of the lithosphere, or surfacing as new oceanic crust at locations where the seafloor is spreading.

However, some rheologists and geologists believe subducted slabs can pierce the transition zone and reach the lower mantle. Other evidence points to the permeability of the transition layer and the material exchange between the upper and lower mantles.

Water

The amount of water in the transition zone of the mantle is perhaps its most significant feature. As much water can be stored in transition zone crystals as there is in the world’s oceans.

It is not “water” as we understand it when it is in the transition zone. None of these describe it; it is not even plasma. Water actually only exists as hydroxide. An ion combining hydrogen and oxygen with a negative charge is called an oxide. Rocks like ringwoodite and wadsleyite, which have crystalline structures, are trapped with hydroxide ions in the transition zone. At extremely high pressures and temperatures, these minerals are created from olivine.

GEOLOGY : The Mantle

Lower Mantle

From 660 kilometers (410 miles) to 2,700 kilometers (1,678 miles) below the surface of the Earth, the lower mantle can be found. Compared to the upper mantle and transition zone, the lower mantle is hotter and denser.

Compared to the upper mantle and transition zone, the lower mantle is far less ductile. Although heat often causes rocks to melt, the lower mantle is kept rigid by high pressure.

Regarding the lower mantle’s structure, geologists disagree. Some geologists believe that lithosphere slabs that have been subducted there have settled. Others believe that the lower mantle is completely stationary and does not even conduct heat via convection.

GEOLOGY : The Mantle

D Double-Prime (D’’)

D’, or “d double-prime,” is a shallow area that lies beneath the lower mantle. D” forms an almost imperceptibly thin barrier with the outer core in some places. D” contains significant concentrations of iron and silicates in other places. Geologists and seismologists have discovered vast melting in other places.

The lower mantle and outer core have an impact on the erratic movement of elements in D’. When more fluid material is driven into brittle underlying rock, a dome-shaped geologic feature called an igneous intrusion called a diapir is formed. This igneous intrusion is influenced by the iron of the outer core. Similar to a lava lamp, the iron diapir gives off heat and has the potential to release a large, bulging pulse of either material or energy. It may even explode as a mantle plume as this energy grows upward, transporting heat to the lower mantle and transition zone.

The core-mantle boundary, or CMB, is located at the base of the mantle, 2,900 kilometers (1,802 miles) below the surface. The mantle ends at this location, known as the Gutenberg discontinuity, and the liquid outer core of the Earth begins.

GEOLOGY : The Mantle

Mantle Convection

Mantle convection is the term used to explain how the mantle moves when heat is transferred from the blazing core to the brittle lithosphere. The mantle’s temperature gradually drops over extended periods of time as a result of below- and above-surface heating and cooling. Convection in the mantle is influenced by all of these factors.

At plate borders and hot regions, convection currents transport hot, buoyant magma to the lithosphere. Additionally, through the process of subduction, convection currents transport denser, cooler material from the crust to the interior of the Earth.

GEOLOGY : The Mantle

Mantle Plumes

An upwelling of extremely hot rock from the mantle is known as a mantle plume. “Hot spots,” which are volcanic zones not produced by plate tectonics, are probably caused by mantle plumes. A mantle plume turns into a diapir as it approaches the upper mantle. Volcanic eruptions are brought on by this molten material heating the asthenosphere and lithosphere. Although tectonic activity at plate boundaries is the main cause of such heat loss, these volcanic eruptions only have a minimal impact on it.

In the center of the North Pacific Ocean, the Hawaiian hot spot is located above what is probably a mantle plume. The Hawaiian hot spot is essentially fixed as the Pacific plate shifts in a generally northwestern direction. This, according to geologists, has enabled the Hawaiian hot spot to produce a number of volcanoes, ranging in age from the 85-million-year-old Meiji Seamount on Russia’s Kamchatka Peninsula to the Loihi Seamount, a submerged volcano southeast of the Hawaiian “Big Island.” The youngest Hawaiian island will eventually be Loihi, which is only 400,000 years old.

Two so-called “superplumes” have been located by geologists. The melt component of D” is where these superplumes, also known as large low shear velocity provinces (LLSVPs), first appeared. Most of the southern Pacific Ocean’s geology is influenced by the Pacific LLSVP (including the Hawaiian hot spot). The vast majority of southern and western Africa’s geology is influenced by the African LLSVP.

GEOLOGY : The Mantle

Exploring the Mantle

Never has the mantle been directly investigated. Even the most advanced drilling technology has not penetrated deeper than the crust.

XenolithsMany geologists study the mantle by analyzing xenoliths. Xenoliths are a type of intrusion—a rock trapped inside another rock. The xenoliths that provide the most information about the mantle are diamonds. Diamonds form under very unique conditions: in the upper mantle, at least 150 kilometers (93 miles) beneath the surface. Above depth and pressure, the carbon crystallizes as graphite, not diamond. Diamonds are brought to the surface in explosive volcanic eruptions, forming “diamond pipes” of rocks called kimberlites and lamprolites. The diamonds themselves are of less interest to geologists than the xenoliths some contain. These intrusions are minerals from the mantle, trapped inside the rock-hard diamond. Diamond intrusions have allowed scientists to glimpse as far as 700 kilometers (435 miles) beneath Earth’s surface—the lower mantle. Xenolith studies have revealed that rocks in the deep mantle are most likely 3-billion-year old slabs of subducted seafloor. The diamond intrusions include water, ocean sediments, and even carbon. Seismic WavesMost mantle studies are conducted by measuring the spread of shock waves from earthquakes, called seismic waves. The seismic waves measured in mantle studies are called body waves, because these waves travel through the body of the Earth. The velocity of body waves differs with density, temperature, and type of rock. There are two types of body waves: primary waves, or P-waves, and secondary waves, or S-waves. P-waves, also called pressure waves, are formed by compressions. Sound waves are P-waves—seismic P-waves are just far too low a frequency for people to hear. S-waves, also called shear waves, measure motion perpendicular to the energy transfer. S-waves are unable to transmit through fluids or gases. Instruments placed around the world measure these waves as they arrive at different points on the Earth’s surface after an earthquake. P-waves (primary waves) usually arrive first, while s-waves arrive soon after. Both body waves “reflect” off different types of rocks in different ways. This allows seismologists to identify different rocks present in Earth’s crust and mantle far beneath the surface. Seismic reflections, for instance, are used to identify hidden oil deposits deep below the surface. Sudden, predictable changes in the velocities of body waves are called “seismic discontinuities.” The Moho is a discontinuity marking the boundary of the crust and upper mantle. The so-called “410-kilometer discontinuity” marks the boundary of the transition zone. The Gutenberg discontinuity is more popularly known as the core-mantle boundary (CMB). At the CMB, S-waves, which can’t continue in liquid, suddenly disappear, and P-waves are strongly refracted, or bent. This alerts seismologists that the solid and molten structure of the mantle has given way to the fiery liquid of the outer core. Mantle MapsCutting-edge technology has allowed modern geologists and seismologists to produce mantle maps. Most mantle maps display seismic velocities, revealing patterns deep below Earth’s surface. Geoscientists hope that sophisticated mantle maps can plot the body waves of as many as 6,000 earthquakes with magnitudes of at least 5.5. These mantle maps may be able to identify ancient slabs of subducted material and the precise position and movement of tectonic plates. Many geologists think mantle maps may even provide evidence for mantle plumes and their structure.

GEOLOGY : The Mantle

Despite years of effort, no one has yet succeeded in drilling all the way to the Moho, which marks the boundary between the Earth’s crust and mantle. Drilling 1,416 meters (4,644 feet) into the North Atlantic seafloor in 2005, scientists with the Integrated Ocean Drilling Project asserted to have come within 305 meters (1,000 feet) of the Moho.

Xenoliths

Many geologists use xenolith analysis to learn more about the mantle. A sort of incursion, a rock imprisoned inside another rock, is a xenolith.

Diamonds are the xenoliths that reveal the most details about the mantle. Diamonds are formed in the upper mantle, at a depth of at least 150 kilometers (93 miles), under highly special circumstances. Carbon crystallizes as graphite, not diamond, above depth and pressure. Intense volcanic eruptions that produce “diamond pipes” of the rocks kimberlites and lamprolites bring diamonds to the surface.

GEOLOGY : The Mantle

Seismic Waves

These waves are measured as they pass through various locations on the Earth’s surface by instruments positioned all around the world. Primary waves (P-waves) typically arrive first, followed closely by s-waves. Different kinds of rocks “reflect” both body waves in various ways. This enables seismologists to distinguish between various rocks that are found deep inside the Earth’s crust and mantle. For instance, deep underground oil resources can be found using seismic reflections.

“Seismic discontinuities” are sudden, predictable variations in the velocity of body waves. The Moho is a discontinuity that delineates the transition between the upper mantle and crust. The border of the transition zone is designated as the “410-kilometer discontinuity.”

GEOLOGY : The Mantle

Mantle Maps

Geologists and seismologists in the present day may now create mantle maps thanks to cutting-edge technology. Seismic velocities are typically shown on mantle maps, indicating patterns deep within the Earth’s crust.

Geoscientists anticipate being able to map the body waves of up to 6,000 earthquakes with magnitudes of at least 5.5 using sophisticated mantle mapping. These mantle maps may be able to pinpoint where certain tectonic plate movements and ancient slabs of subducted material are located. Many geologists believe that mantle maps could even offer proof of the structure and motion of mantle plumes.

GEOLOGY : The Mantle

Facts about Mantle

- Active Mantle of the Earth Only the planet Earth has a continuously active mantle in our solar system. Both Mercury and Mars have stable internal architecture. Venus has an active mantle, but because of the way its crust and atmosphere are built, it does not frequently alter the planet’s topography.

- Explosive Research Similar to earthquakes, explosions cause seismic waves. Strong nuclear explosions may have left behind body waves that held hints about the Earth’s innards, but this type of seismic research is forbidden by the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty.

- Conductivity Mantling Instead of seismic waves, some mantle maps show electrical conductivity. Scientists have aided in locating subterranean “reservoirs” of water by monitoring electrical pattern disruptions.

GEOLOGY : The Mantle

Read also : What is Megafire?

The First Encyclopedia Your First Knowledge Home

The First Encyclopedia Your First Knowledge Home